21. Dec 2022 - DOI 10.25626/0143

Patrick Metzler is currently obtaining an MA-degree in History and Politics at the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena. His main research interest is in the field of politics of memory and commemoration in Germany and Central Europe. He has been working as a freelancer for the Ettersberg Foundation, Erfurt and as an assistant to the research project Diktaturerfahrung und Transformation at the University of Jena. Since 2020, he is responsible for public and visitor relations at the Laura memorial – former subcamp of Buchenwald.

On 18 November 2021, the new permanent exhibition “Naši Nĕmci / Unsere Deutschen” (Our Germans) in the city of Ústí nad Labem (Aussig an der Elbe, as it was previously called in German) finally opened its doors to the public. Among the speakers at the opening ceremony were the Czech minister of culture, Lubomír Zaorálek, and the prime minister of Saxony, Michael Kretschmer – although he was not the first German politician to tour the exhibition. Just a few months earlier, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier had visited the exhibition, which hints not only at the high expectations attached to the project, but also at its importance to the bilateral relations between Czech Republic and Germany.

The opening ceremony was a milestone in a political and curatorial process that spanned several decades. Since the end of the Second World War, dialogue surrounding certain painful events in German-Czech history – in particular the war-time Nazi protectorate and the postwar expulsions of Germans from Czech territory – was difficult and marked by disputes and mutual recriminations. With the end of the Cold War, relations improved, and, in 1993, a trilateral Czech-Slovak-German historical commission began to jointly research the most difficult aspects of their shared past. In 1997, the German-Czech Declaration on Mutual Relations was adopted;[1] it acknowledged the German aggression against the Czech people and declared that bilateral relations should no longer be burdened by the past (including any legal claims). However, a plan to address this shared history in form of an exhibition did not emerge until 2006. The idea took shape with the establishment of the Collegium Bohemicum – with the support of the city of Ústí nad Labem, the J. E. Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, the Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Deutschen in Böhmen (the society for the history of Germans in Bohemia) and the Czech Ministry of Culture, where Czech, Austrian and German historians began to conceptualize a permanent exhibition focusing on German life in Bohemia from a decidedly Czech perspective, as set out on the official museum website. The project was funded by (among other sources) the Czech-German Future fund, an institution founded as a result of the 1997 declaration. Political quarrels and changes in the curatorial team delayed the opening of this ambitious project, which took fifteen years to complete. The curators of the newly opened exhibition argue that the current exhibition is not the final version of their original vision.

The city of Ústí nad Labem is located about midway between Prague and Dresden. Once a city with a predominantly German population, today's industrial townscape reveals few traces of its German history. The German name of the city, Aussig, has a tragic ring for many Germans who once called the city home. In July 1945, the city witnessed one of the most brutal outbreaks of violence against German residents, when Czech militia and townspeople expelled their neighbours and killed over one hundred in what is sometimes referred to as the “Aussig massacre”.[2]

The museum building is a significant exception to the otherwise dominant impression of a town scrubbed of its German past. Located in a late nineteenth-century building, visitors are greeted in the entrance hall by German language slogans – left over from its previous incarnation as a German school – that declare “Gott mit uns” (God with us) or “Bildung macht frei” (education liberates). Although the building served as the city museum of Ústí nad Labem for decades, the entrance hall now serves as a fitting introduction to the narrative of the new exhibition: German cultural contributions to an area now mostly devoid of Germans.

The timespan addressed in the exhibition goes beyond the focus of this review. While the chronology of the exhibition begins in the Middle Ages, the main focus here is on the mid-nineteenth to twentieth centuries. The author visited the museum as part of a tour given by one of the curators, allowing for a deeper look ‘behind the scenes’.

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor is led into a room where a five-minute introductory film sets the narrative for the thematic modules of the exhibition. In the film, seemingly randomly selected items are introduced by a soft-spoken narrator, who invites the viewer to figure out “what all these things have in common,” before the volume and velocity of the film increase markedly, as the perspective shifts to a bird’s eye view of an illustrated map on which the names of the cities change from German to Czech. The answer to the initial question seems quite obvious, given the room’s guiding motto “Who are our Germans?”: The items are all connected to Germans who once lived in Bohemia and contributed culturally to the region.

Among the Germans introduced, Franz Kafka stands out as the most prominent “German language writer”. This seems somewhat of a provocative standpoint, given Kafka’s well-known multiple identities as a self-proclaimed German Jew and German-speaking Czech. While his multifaceted identity is addressed in the film, he is nevertheless specifically included in the overall narrative for his “Germanness” – a provocation that curator Petr Koura readily acknowledged during a public debate in December 2021 after he was criticized for allegedly ignoring Kafka’s Jewish background. This choice by the curators can be explained by a (historic) Czech perspective that focusses on language as the main marker of ethnic identity, whereby ‘Jews’ in Czechoslovakia were often referred to as Germans, since most spoke German at the time. Nonetheless, the example highlights the difficult and often fluid nature of national identities that existed in interwar Central Europe, as well as the significance of their attribution in the later events detailed in the various thematic rooms.

Before continuing onwards, an unexpected curatorial element catches the visitor’s eye: The moment the film ends, a large showcase is revealed behind the screen, exhibiting the very historic artefacts presented in the film. This sleight of hand creates a special effect and reveals that the curators did not rely exclusively on the extensive use of modern multimedia elements, but also succeeded in gathering numerous authentic objects that were intelligently integrated into the overall narration.

This reciprocal use of technology and artefacts continues throughout the exhibition, which at first follows a mostly chronological order. Separate thematic modules are integrated into the halls of the historic school building. After the introductory film, visitors are immersed into a rather cosy (heimelige) atmosphere made up of carved up wooden trunks – which serve as stands for a wide array of romantic nature paintings (Landschaftsmalerei) by German artists – and extensive media installation made up of multiple projectors and a sound system simulating a “forest and hills”-environment. A connection to the film is made through a reference to the “Altvater- and Riesengebirge” (the fatal race of two Czech skiers in 1913 is mentioned in the film) and the presentation of Emmerich Rath’s skies. Written in simple black letters on the white wall, the room’s central question also makes use of this connection to the Altvatergebirge, asking: “Where is my home? My fatherland?” Such thematic questions are used throughout the exhibition not only to separate the thematic arrangements but also to create a contrast with the otherwise heavy focus on installations used to contain and enact the exhibits themselves. While most of the historic artefacts in this room are placed in the middle, on one wall, media stations project collections of newer photographs, shot as a part of a contemporary project that revisited various historic sites. The link to the present is meant to illustrate that the current absence of Germans in the region is always present – not only in the exhibition.

Revolution and National Awakening

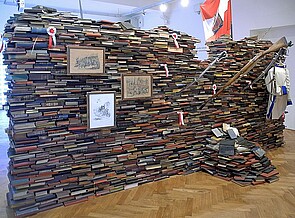

Leaving behind the ‘forest’, a sudden turn of events takes place, as visitors are confronted with the rising nationalism of the revolutionary events of 1848-1849. A strong focus on enactment becomes visible here, more so than in any of the other spaces, with barricades built of numerous old books in Czech and German splitting the room in two halves. The barricades are speared by bayonets, swords and flagpoles – an installation that is somewhat contextualized by individual papers integrated into the installation. Placed around the books, these papers are copies of historic pamphlets distributed during the revolutionary events of 1848, and thus give an impression of the political climate surrounding the conflicts of the time. The stark contrast between the two rooms – the forest landscape and the barricade – gives the impression of an idyll destroyed by revolution and its progressively nationalistic undertones, separating the conflicting parties – Czechs and Germans – not only by class, but especially by language. As portrayed in the exhibition, language now becomes the main denominator for national identity and for the conflicts that arise, reflected in the books making up the barricade, which also symbolically divide society. By using rather easily recognisable representations of the conflict in questions, the necessity for extensive information appears to fall by the wayside in this room.

Pride at the End of an Empire

An element of enactment is also visible in the next space, as visitors experience the consequences of the revolutionary events by entering a small furnished parliament, with portraits of parliament members along the main wall. Some of the portraits are animated, greeting the viewer with moving faces – an irritating feature that demonstrates the possibilities of modern technology more so than the possibility of increasing our understanding of the historical context. More traditional media is also present, in the form of speakers that replay quotes from contemporary parliamentary speeches. Those who want to listen can follow a short debate in the Böhmische Landtag – and even ‘interfere’ when disagreeing with the speaker’s position or ‘calling for order’ by using a small device mounted to the table. This interactive element shows the occasionally quite playful character of the exhibition. Similarly, when moving past the portraits and around the rows of seats, visitors find that the backs are used as cabinets displaying historic artefacts. Some of these artefacts are not immediately visible, but hidden behind small wooden doors. Visitors are thus invited to interact with their surroundings and explore the cabinets, which contain a wide range of objects, from national flags to political declarations to personal commemorations of soldiers serving in the First World War. Among the portraits of parliamentarians is a significantly larger portrait of Božena Viková-Kunětická, the first Czech woman to be elected to the Landtag. Yet her portrait is somewhat hidden from view which points to the fact that she was actually barred from taking her seat, as Austrian imperial law excluded women from political participation. This example shows the immensely dense and detailed representation of the political and social climate of Bohemia in the later days of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy before it came to an end in 1918.

Democracy and Chauvinism

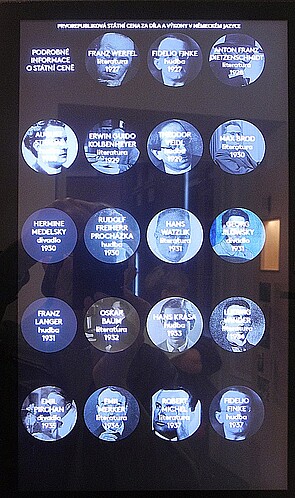

Moving chronologically, the next space presents the upheavals of the young Republic after its establishment after the end of the First World War. Certain individuals, familiar from the preceding room, reappear as they played integral roles in the conflicts and political struggles of the newly formed democratic state of Czechoslovakia. Especially the first president of the Republic, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, is prominently displayed with a statement from 1925 that “politically, the German minority is the most important group.To win them for the Republic will alleviate all other minority questions.”[3] This statement, written across one of the walls, is supposed to show how the Czechoslovak elite tried to reach out to the increasingly distant German minority, but also called for their integration for the benefit of the state as a whole. Other displays in this room make clear how this effort was increasingly jeopardized by the rise of chauvinistic movements, such as that of Konrad Henlein, which found trusted allies in the growing National Socialist Movement in Germany. Visitors are led through a labyrinth of propaganda-plastered wooden cabinets that, in their rather chaotic appearance, stand in contrast to the seemingly ordered parliament witnessed earlier. Visitors thus find themselves in a highly divided society, where cleavages run along a complex amalgamation of national, class and religious identities, where numerous political parties compete for sometimes oddly specific target groups, and where Henlein’s Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront succeeds in gathering an increasing number of supporters – symbolically represented by the space his movement takes up in the exhibition room. In addition to the openly antisemitic statements articulated first and foremost by the German nationalist movement, any Jewish perspective remains more or less in the background. While the exhibition notes that Jewish communities organised their own political parties and associations, with German as their primary language of communication, they do not appear in any visible way. As the exhibition largely avoids discussing aspects of national and ethnic identity and their internal and external attribution, the issue of Jewish political and social life could have been addressed in greater detail, as it is vital to understanding the various conflicts of the time. Yet its circumvention may point to the hostile climate that Jewish communities were confronted with, cornered between antisemitic and anti-German resentments. This climate becomes apparent to the visitor through the openly antisemitic and chauvinist imagery contained in the propaganda material displayed.

The “Protektorat” – German Military Rule

The consequences of these inter-ethnic resentments become visible in the next room, which covers the era of the Protektorat, the factual German military occupation of current Czech territory, which began in 1938 and ended in 1945. These years are recounted through wooden enclosures that separate the space into three sections, each containing artefacts and detailed explanations. One of the most impressive installations, which immediately catches the eye upon entering, is a photo-collage of portraits of Jewish residents. Some of the pictures are in black and white, others in colour – showcasing survivors (in colour) and victims (in black and white) of the Shoah and revealing the extent of the German extermination programme in the region. In the second space, various propaganda materials are on display, next to pictures depicting acts of resistance and perseverance – such as artefacts owned by individuals imprisoned at Theresienstadt and by those involved Czechoslovakian partisan-movements. In the third space, visitors are confronted with artefacts related to the Germanification under National Socialist rule, such as armbands and ribbons. This collection is complemented by the story of Oskar Schindler. He is introduced as a Moravian-born German, and his story is told through a copy of his “list”, reported to have saved the lives of Jewish prisoners by exempting them from transports to Auschwitz by employing them as unpaid workers in one of Schindler’s factories.

The extent of German cruelty is exemplified by a window that opens onto photographs of victims of the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Mittelbau and their subcamps as well as the ‘death marches’, taken by US forces. The pictures are hidden behind black movable boards, and it is left to the visitor to decide whether to directly confront the images of dead bodies and charred remains. It remains an open question whether, for the sake of dignity of the victims, these images should have been displayed differently, or not at all, since there are new technical solutions, which, for example, could have blurred the image of the bodies, while retaining their shocking effect. These pictures are also the last shown, and thus create the transition to the last thematic room of the exhibition: The resettling of the Germans.

As reflected in the reactions of the group on the tour, this final room – depicting the forceful resettlement of Germans from their homeland in Bohemia and Moravia between 1945 and 1947 – might also be one of the most intense and most difficult to curate, in terms of the inherent conflicts of commemoration. For many years, this episode was the basis for recurring bilateral disputes, often revolving around the legality of the so-called “Beneš decrees” – a series of laws originally drafted by the Czechoslovak government-in-exile and retroactively ratified by the postwar Czechoslovak National Assembly in 1946, which formed the legal framework for the expulsion of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia after the War. In West Germany, a number of German expellees organized themselves into Landsmannschaften, which argued for the unlawfulness of these decrees and for the recognition of the violence and brutality of their expulsion. Meanwhile in communist Czechoslovakia, the resettlement of the Germans was considered to be in accordance with the law at the time, with the violent aspects of the resettlements denied or simply ignored. Even after 1990, the violence remained widely unaddressed. Thus, the German-Czechoslovak ‘Treaty of Good Neighbourship signed by Helmut Kohl and Václav Havel in 1992 referred only vaguely to the obligation to commemorate “the victims of wars and violent rule”.

The Beneš decrees are central to the last room – displayed on a wooden wall, their content and consequence explained in a rather lengthy text. They are presented as laws that shaped the future of the German populace by codifying, among other things, the right to expel Germans in response to their collaboration with the Nazi occupation authorities. An already well-known cabinets take on another dimension in this context. Behind their doors, visitors now find a collection of belongings left behind by Germans forced to leave their homes in 1947. These objects tell their own stories and can be understood as a reference to a history of loss hidden away behind closed doors; that visitors must uncover the objects for themselves by opening the doors to get a glimpse of this history.

The documentation of the expulsions through items left behind and the trunks of resettled Germans brings up associations to the photographs of the concentration camp victims seen in the previous room. While these may be intentional, they also leave behind an uncomfortable feeling, as it risks blurring distinct historical and ethical boundaries. Leather trunks and displays of personal items are often a trope used in exhibitions that focus on the Holocaust – the mass deportations of Jews from across Europe. This association, if intended, can be read as a representation of cause and effect – German crimes as the cause for their own subsequent deportation -- that reveals a clear shift from focusing on the “perpetrators” to focusing on what was “perpetrated”. In a way, this association can be seen as a successful curatorial move – to create a space that tries to open a previously taboo topic to factual debate and avoids a one-sided view by providing extensive information on the historical events without resorting to an overly judgemental tone. An interesting fact, not included in the exhibition but mentioned by the tour guide adds to the complexity of this exhibition room: Parallel to the resettlement of Germans, other groups were also resettled, among them Roma that survived the German genocide programme. After fleeing from regions further east to escape Nazi rule, they became a major group that took over formerly German homes and farms as part of an intentional programme supported by the new Communist government as a means of rebuilding the workforce following the German emigration.

Next to the chronological tour, there are also separate thematic rooms that further detail and deepen aspects addressed in the main exhibition. One, which is clearly addressed to a German audience, explains why the word Sudetendeutsche commonly used in German to describe the former German minority in Czechoslovakia was not used in the exhibition. From a Czech perspective, they were all ‘simply’ Germans by language and thus a geographical categorization would be misleading. This view is supported by the argument that while ‘German’ might be the common denominator for to this population, it still serves as a depiction of various groups who once lived in Bohemia and Moravia, sometimes highly diverse in their dialect and cultural practices, differing according to distant and separate regional environments. One media station makes this point very clear, as visitors can press buttons on a map of the region and listen to voices with widely varying dialects.

Another interesting facet of the exhibition are the walls of the hallways that lead from one exhibition area to the other. They are decorated with a long comic strip that recounts the same history, but from completely different perspective than the main exhibition rooms. While most of these drawings portray the various historical episodes in a humorous way, depicting boozing Germans and a violin-playing Albert Einstein, a decent amount of dark humour is needed to absorb the sometimes raw violence they contain, including episodes such as a Kindertransport (the deportation of children), the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and the public humiliation of Germans and alleged collaborators in 1945. These drawings, only supported by mostly purposely miswritten exclamations, reveal how history can be told and displayed in widely different ways, while also complementing the experience of the visit through their counterplay – an aspect that definitely invites for further discussion on the suitability of the artform for the topics at hand.[4]

In conclusion, one can say that, considering the difficulty of the task, the curators succeeded in creating a dense, atmospheric, and multifaceted exhibition. Using modern technology that in some places appears as a mere gimmick (like the moving images of members of parliament), the exhibition nonetheless never becomes too overwhelming, mostly maintaining its character as a history museum. The impression remains that the contextualization provided and, despite its often playful nature, the interactions between visitor and material counteract the possibility of mere emotional stimulation. But there is also talk of a yet to be finalized exhibition: To quote the curators, there are still open spots and coming additions. A promised catalogue has yet to be published. There is thus a much to anticipate and reflect on.

Patrick Metzler: Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem. Cultures of History Forum (20.12.2022), DOI: 10.25626/0143.

Copyright (c) 2022 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Karolína Bukovská · 25.11.2021

(Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twent...

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 21.07.2021

Czech Prime Minister Implicated as Communist Secret Police Agent – Yet Nobody Cares

Read more

Jakub Vrba · 18.12.2020

Monumental Conflict: Controversies Surrounding the Removal of the Marshal Konev Statue in Prague

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).