01. Jun 2017 - DOI 10.25626/0064

Nutsa Batiashvili is an assistant professor in social sciences and Dean of the Graduate School at the Free University of Tbilisi. In 2016 she received a one-year postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oxford, School of Interdisciplinary Area Studies. She has an undergraduate (2004) and an MA (2006) degree in Social Psychology as well as a PhD (2014) in Anthropology from Washington University in St Louis. Her current research is situated at the intersection of cultural anthropology, political anthropology, interdisciplinary memory studies, linguistic anthropology, studies of nationalism and post-Soviet transformation.

The Tbilisi Museum of Soviet Occupation, which opened in 2006 as a subsection to the Georgia National Museum, is a site of mnemonic contestation where the Soviet past is being displayed in a manner meant to reflect current disputes over politics and memory. This article discusses some of the discourses behind the museum’s current permanent exhibition in relation to Georgia’s geopolitical mission to become European, mend relations with Russia and overcome internal political friction.

“Look at this one, this is the door of Stalin's prison cell, when he was imprisoned,” said Nikoloz Rurua, Georgia’s former Minister of Culture and the originator behind Tbilisi’s Museum of Soviet Occupation,[1] while pointing to a steel-framed wooden door on display as one of the centrepieces of the exhibition, “and this one is already from the period when Stalin ruled the Soviet Union. Do you see the difference?” The second door was made of solid steel, and the comparison between the two types of prison doors was meant to symbolically underline the move towards complete terror that the USSR took with the rise of Stalin. “It’s ironic,” Rurua said with a smirk meant to elude to the specifically Georgian context in which the figure of Stalin remains a multivalent mnemonic symbol: for some Stalin is the bare embodiment of evil, for others a brilliant mind who brought the ultimate victory to the world, and then there are those proud Georgians for whom Stalin is just ‘a Georgian guy who ruled half the planet’.

It is not only the figure of Stalin, but the entire history of Soviet rule and Russian relations that some refer to as the “difficult past.”[2] There are many reasons for this, some of which have to do with colonial and postcolonial forms of subjectivity, post-socialist nostalgia, and sense of uncertainty brought by the changing regimes of social order. This may have to do with Stalin's Georgian nationality and Russia's Orthodox Christianity and the resulting, often insurmountable, sense of empathy and kinship that these traits produce for certain publics in Georgia. Both of these attitudes are, of course, politically hazardous from the perspective of the state. This is especially evident in the aftermath of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war where pro-Russian and/or pro-Stalin sentiments became distinctly unsettling to the Western-oriented administration of then President of Georgia, Mikheil Saakashvili. The ways in which these attitudes infringe upon the unanimity of the national will to Euro-integration, and stand in the way of the dominant political agenda, has been part of the political discourse in Georgia for quite some time. These issues become exceptionally charged as they implode into memory disputes. It is here, in the realm of memory that one can discern how Stalin, the Soviet Union or Russian occupation is understood in terms of embedded cultural gambits.

Museums are, of course, only one form of material representation capable of providing ‘a vision’ into the past by way of cultivating socially embedded cultures of memory. But they are also acute concretizations of the nexus of politics and memory. The Tbilisi Museum of Occupation inhabits this vein and therefore provides an interesting example. The way in which the permanent exhibition engages specific representations of the past demonstrates its reliance on circulating forms of discourse regarding historical and fixed memory narratives. Later, I will discuss which elements have meaning in the context of cultural symbols, such as national narratives. At the same time, the Tbilisi Museum of Soviet Occupation represents a specific political project within the pro-European agenda of Saakashvili’s administration. As such, it is not merely an embodiment of a nation’s memory narrative, but is itself a compilation of politically charged statements targeting particular audiences and particular discourses.

Due to financial restraints, the Tbilisi Museum of Soviet Occupation does not inhabit a separate building and is instead housed within the National Museum. As a result, its permanent exhibition is confined to just two dim and dismal, red-coloured exhibition rooms. Another element that distinguishes it from other occupation museums in Eastern Europe, such as those in Tallinn and Riga is the fact that the museum is publicly funded.[3] Whereas other Baltic Occupation Museums try to reinforce the narrative of occupation, while simultaneously providing an image of what lived experience was like under the Soviet structure, the Tbilisi museum focuses exclusively on reinforcing the metanarrative of Russian occupation. This is due to the fact that the programme of the Tbilisi Museum of Occupation has a distinct ‘moral impulse’ which it attempts to convey by addressing two separate publics, with two separate messages. The first moral impulse is to debunk the positive, or rather ambivalent, narratives about Russia and Stalin, the most overt claim being: ‘Russia is and has been a violent, ruthless enemy to the Georgian nationhood’. The denigration of Stalin is part of this claim; also targeted are the more amiable interpretations of Stalin’s figure. Most importantly, the attempt to portray him as a mastermind behind the purges and massacres stands in contrast with the narrative that accentuates Stalin’s virtuous leadership skills and his role in defeating Nazi Germany. The centrepieces of the exhibition – those items that occupy the prime location and exhibit most in terms of visual magnitude – are the aforementioned prison doors, an imitation of a prison cell and a massive writing desk, all of which generate symbolic clues pertaining to the figure of Stalin. The theme of a terrorizing regime is represented alternatively through such staged representations vis-à-vis textual narrations. The exhibition is punctuated by display tables that provide information on periodic purges that took place in the Soviet Union and a map of the ‘Gulags’ behind Stalin’s desk. Along with these items are portraits of Stalin and quotes by him. This staging effect spawns the image of a mastermind, who from behind his desk, singlehandedly plotted the Soviet terror. The timeline of the exhibition begins with the first Socialist Democratic Republic (declared in 1918) and ends with the nationalist movement of late 1980s and the gaining of independence in 1991. The space allocated to separate historical periods is not coherent or systematic. This, in its own right, provides a clue as to the agenda of the museum and suggests that rather than being structured methodologically by professionals, it was instead conjured up in the minds of critically engaged public figures and politicians. This is why the representations are sporadic and at times unstructured.

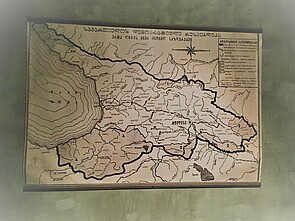

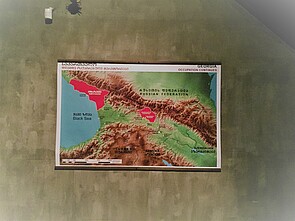

There is a second message running through the exhibition, however, and it is somewhat parallel to the Stalin-critical agenda, as the museum was designed to signify Georgia’s ‘European-ness’ and to establish its place in the narrative of European history vis-à-vis Soviet/Russian history. Some of the exhibits describing the Democratic Republic of Georgia, declared in 1918, provide limpid demonstration of this. One such display highlighting Georgia’s historic linkage to the European community is an early twentieth-century map of the Georgian borders as recognized by the League of the Nations. Following this, is a panel showcasing the instrumental roles that figures like Sir John Oliver Wardrop, the United Kingdom’s first chief commissioner of Transcaucasia in Georgia, and Friedrich Schulenburg, the consul of Germany in Georgia, played in drafting Georgia’s 1918 constitution. These stand as reminders of Georgia’s longstanding European aspiration.

Thus, the museum’s aim is to provide a space for reconfiguring how ‘foreigners’ (especially ‘Westerners’) situate Georgia between the East and the West, or between European and post-Soviet space. Several of the exhibits – and their arrangement in relation to one another – construct a statement that aligns Georgia with the rest of the Eastern European states and reinforces the conception that the country had been annexed just as brutally and unlawfully as those who currently have a place in the EU. Thus, the implicit message of the museum is that Georgia rightfully deserves to detach itself from Russia’s imperial margins.

As we stood in the hall of the Museum of Occupation in Tbilisi, Rurua handed me five copies of the booklets he obtained from the curator. In his opinion, part of the story that was missing from the exhibition could be found in this booklet, a re-print of a Special Report by the United States House of Representative’s Eighty-third Congress on the “Communist Takeover and Occupation of Georgia.”[4] In 1953 the US House of Representatives created a special committee to investigate the incorporation of the Baltic states into the USSR; the report on the state of affairs in Georgia was part of that document. Following House Resolution 346, the House Select Baltic Committee – what was known as the Kersten Committee – was established to oversee the investigation chaired by Charles J. Kersten. The existence of the committee was significant for US ‘non-recognition’ politics, but also for better comprehension of the communist methods for the expansion of power.

The report, published both in Georgian and in English, was instrumental in framing the narrative of occupation in legitimate language. The Kersten Committee report functions here as an ultimate validation of the narrative of occupation sealed by the authority of the US government. It represents legitimate proof not only for the Georgian audiences but for the foreign ones as well.

The Tbilisi Soviet Occupation Museum opened on 26 May 2006. At the opening ceremony president Mikhail Saakashvili stated the following:

This Museum is dedicated to the great patriots of Georgia, Kakutsa Cholokashvili, and his sworn brothers. This museum is dedicated to a number of underground organizations that were created throughout this period. This museum is dedicated to the Georgian clergy, the better part of which has been almost entirely exterminated. This museum is dedicated to Georgian officers. This museum is dedicated to my great grandfather Nikusha Tsereteli, in whose family I was raised and who spent many years in one of the camps in Siberia.[5]

At the time, Saakashvili’s statement capitalized on the main thematic points of the museum; and his words entered into dialogue with many other voices present in Georgia’s discursive space. Yet, in terms of semantics, the rhetorical line of both the museum and Saakashvili are built on pre-existing cultural symbols. Karp and Lavine have rightly asserted that “every museum exhibition, whatever its overt subject, inevitably draws on the cultural assumptions and resources of the people who make it”.[6] This implies that whatever the political agenda of the state, the narrative constructed by the museum takes place against a backdrop of existing cultural myths. Telling a story – almost any story – is guided by a narrative habit.

While the Museum of Occupation was determined to tell the story of Soviet occupation and was conceived as part of the political program of the president, its plotline instead follows a narrative pattern highlighting alternative stories of foreign invasion and occupation. Indeed, the Georgian national narrative capitalizes on stories of resistance and the perennial struggle for freedom against continuous foreign invasions.[7] In its most schematic representation, both Russian imperial rule and the Soviet regime are part of a single occupation story and represent just another instantiation of invasion by alien forces that Georgians have resisted and rebelled against, along with Mongols, Arabs, Persians, Ottomans, Seljuks, and so forth. This narrative plot functions as an underlying ordering structure in the exhibition. This is why Saakashvili mentions Kakutsa Cholokashvili in his speech – a figure that symbolizes heroism and rebellion against foreign regimes. In the exhibition, Kakutsa Cholokashvili’s dress is displayed in a glass coffin, below a screen displaying images of the events in August 2008. Because of its limited resources, the Museum of Occupation employs some very generic forms of representation, but in essence the storyline it conveys is tied to the mythology of the Georgian nation. As such, the entire exhibition can be read simply as another instance of the Georgian national narrative.

The beginning of the museum narrative is tied to the imagined geography of legitimate Georgian territories. Opposite the map that shows the borders recognized by the League of Nations. there is another map featuring the current Georgian territory with its conflict-ridden, secessionist territories lit in bloody red. The wall space between the maps is allotted for the memory of the anti-Soviet resistance and the story of eminent freedom fighters between 1921–1991, juxtoposed with factual information on purges and forced migrations. This information specifically highlights the execution of eminent members of the intelligentsia, clergy and noblemen. This information specifically highlights the executions of what one visitor commented as “[…] the very best of the nation […] noblemen and intellectuals”. Along with the addition of clergy and intelligentsia to the execution list, her impression was an ample reading of the intended narrative.

At the end of our three-hour-long conversation and tour I asked Rurua what primary narrative he intended the museum to convey. He responded with a lengthy and eloquent answer, providing a palpable concretization of the political, ideological and moral objectives of this site of memory:

The narrative of the museum should be to demonstrate, to our audience, the hefty Russian tendencies in the systemic destruction of the Georgian identity, so that people deprived of identity would not have any desire for an independent state. We wanted to show, based on facts, that Russia did everything through the so-called radical ‘social engineering’ to mould a Soviet-Georgian species, emptied of national memory and ideals. We, the authors of the museum, wanted to demonstrate this through concrete factual evidence, by showing, for instance, how many clerics have been prosecuted and executed by the Bolshevik regime, how many members of Georgian aristocracy and military elite have been murdered and so forth, for the purpose of the erasure of this memory. Our aim was to explain that contemporary Russian goals are in essence not any different from the aims of Bolshevik Russia, even though today Georgia is an independent and democratic state. In short, by using historical context, we wanted to explain where today’s occupation of our territories originates from, as well as [show] what the effortless concession of freedom can bring [to] the nation.[8]

As evidenced by the vast scholarship on museums, public museums are intimately tied to the instruments of governmentality and citizenship.[9] This point cannot be better demonstrated than it is in the quote above, which describes that when national identity, religion and cultural spirit are in danger, it can trigger some of the deepest vulnerabilities and archetypal anxieties of the Georgian nation. There are multivalent and multi-vocal resonances in his words: they formulate a critical response to existing discourses that attempt to create a tolerable image of Russia and the USSR, especially by capitalizing on the shared religion of Georgians and Russians. In the end, Rurua’s concluding remarks demonstrate unequivocally that the museum is a rhetorical device intended as a prohibitive call against ‘effortless concession’.

Museums, in their capacity to create visual representations of the social order, play an important role in regulating imaginative horizons of culture, nation, and citizenship. In her extensive analysis of museums, Mary Bouquet noted:

[N]ational museums and collections underwent an important reconfiguration in the twentieth century as newly independent nations hastened to present their international credentials in this form, and older nations began to rearrange their collections and their connections within the postcolonial world order.[10]

In certain respects, the Tbilisi Museum of Occupation is an instance of both configurations. On one hand, it provides transnational ‘credentials’ for Georgia’s geopolitical determination and for the definition of its historical and political belonging. On the other hand, it presents a ‘rearrangement’ of the symbolic representations to fit the current political agenda. A comment made by Georgian historian Lasha Bakradze, resonates with this point saying: “[…] since the entire Georgian territory was occupied we can imagine this whole territory as a ‘museum’ and create the ‘topography of terror’, which in its own turn will better explain what the Soviet Occupation was.”[11]

Nutsa Batiashvili: Sites of Memory, Sites of Contestation: the Tbilisi Museum of Soviet Occupation and Visions of the Past in Georgia. In: Cultures of History Forum (01.06.2017), DOI: 10.25626/0064.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Official website of the Museum of Soviet Occupation in Tbilisi, part of the Georgian National Museum

See also the websites of the Museum of Occupations in Tallinn, Estonia, and of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia in Riga, Latvia

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).