28. May 2020 - DOI 10.25626/0113

James Krapfl is an associate professor of European history at McGill University and an affiliated researcher in historical sociology at Charles University. He is completing a cultural history of the late 1960s in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and the GDR while anticipating a new project on Europe since 1989. He previously authored the prize-winning book Revolution with a Human Face: Politics, Culture, and Community in Czechoslovakia, 1989-1992.

Andrew Kloiber earned his Ph.D. at McMaster University (Canada). He is completing a book on coffee drinking in the GDR and how the state’s attempts to maintain supplies of the beverage led it to conclude long-term projects to build coffee industries in developing countries. Together with James Krapfl, he is embarking on a second book project, surveying the history of commemorations of the 1989 revolutions in the countries here discussed.

In the kindred revolutions of 1989 in East Germany and Czechoslovakia, millions of mobilizing citizens gained experience as democratic authors of their own history, forcing the pace of change and transcending the paradigm of elite-led ‘refolution’ established in Poland and Hungary.[1] Does this widespread, intense experience of civic engagement help explain why Germany and the Czechoslovak successor states have resisted the democratic erosion apparent elsewhere in central Europe? They have not been immune – as shown by a resurgence of right-wing extremism in Germany, abuse of power allegations against the Czech president and premier, and the 2018 murder of a Slovak journalist for exposing his government’s mafia ties. Yet civic defence of democratic institutions remains effective. If experiences of civic power in 1989 continue to play a role in preserving constituted freedom and the rule of law, it can only be because the memory of those experiences remains vibrant. How vigorous, therefore, are memories of the revolution in eastern Germany and the Czechoslovak successor states, and how do they reinforce democratic politics today?

The thirtieth anniversaries of the Peaceful (German), Velvet (Czech), and Gentle (Slovak) Revolutions provided an excellent opportunity to answer this question. Previous round anniversaries had occasioned bursts of commemorative festivity and public discussion of the revolutions’ significance; would this tradition remain strong in 2019, or would temporal distance dampen desires to recall the past? We observed commemoration first-hand in four cities that played decisive roles in 1989 – Leipzig, Berlin, Prague, and Bratislava – and we have supplemented our observations with journalistic accounts, interviews, and video-recordings. Despite some routinization of commemorative forms, revitalization of what can only be called a revolutionary tradition was much more in evidence, in inspiring response to the contemporary global crisis of democracy.

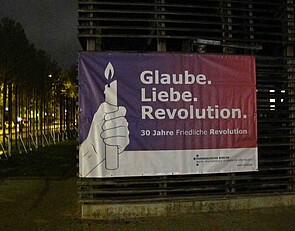

Leipzig in 2019 continued a long-established anniversary tradition of emphasizing civic responsibility. The breakthrough of 9 October 1989 that precipitated Germany’s Peaceful Revolution began with peace prayers in Leipzig’s Church of St. Nicholas (Nikolaikirche), followed by a candlelit march of over 70,000 through the streets ringing the Old Town, chanting “No violence!” and “We are the people!” after police and military intervention was at the last minute averted. Re-enactment – or more precisely, perpetuation – has always figured prominently in the city’s commemorations. The Nikolaikirche’s Monday prayers for peace, which started in 1982, have never stopped, though since 1990 a special service has always been held on 9 October. Public discussions of political themes, recalling the dialogues of 1989, have been recurrent anniversary features. Since 2009, moreover, the city has sponsored an annual ‘Lichtfest’, or light festival, featuring a recreation of the original march.

The centrality of Leipzig’s churches in anchoring interpretations of the revolution is one reason why the city’s commemorations have consistently focused on timeless, universal values. Morning schoolchildren’s peace prayer (Friedensgebet) in the Nikolaikirche every 9 October since 2009 illustrate these interpretations and how they are being passed on. The 2019 service featured a group of students stomping up the church aisle, boisterously chanting “no violence” and “we are the people” as if to re-enact the march of the 70,000 – except that they ended by raising clenched fists. At this point another student appeared, holding a lit candle. This child approached one ‘protestor’ at a time, gently pulling down raised arms and unclenching fists, guiding each hand to grasp a small, lit candle, before the children resumed their march around the church and back to their seats. The dramatization provided a powerful reminder that means, as culturally constitutive expressions of agency, are as important as ends. In her sermon, Rev. Grit Markert described the fear and anxiety she and others had felt in 1989, but also strength through fellowship. “We had real power then”, she reflected, encouraging the schoolchildren to “Be the hand that writes history and changes our world for the better. Your own ‘little power’ can have a surprising influence if you’re willing to try."[2]

Perpetuating the revolutionary tradition of dialogue was an autumnal calendar packed with anniversary-inspired discussions. The Peaceful Revolution Foundation, for example, convened an ‘International Round Table’, which issued a Memorandum for Freedom and Democracy on 9 October. Passers-by were invited to post responses to the question “What causes me anxiety?” producing such answers as “AfD” (the nationalist Alternative for Germany, Alternative für Deutschland), “USA”, and “that we talk to one another so little”. In delivering the 2019 Democracy Address, a 9 October tradition in Leipzig since 2001, Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier singled out round tables as one of the innovations of 1989 that should be revitalized at “a time when we are worried about the future of our democracy and the democracy of the future has not yet taken shape.” “Round tables instead of non-stop indignation and hate speech – that is the right way to keep our democracy strong.” Steinmeier reiterated the theme that doubts and fears of violence had been widespread before October 1989, but then “fear switched sides. The few became many.” In a country where citizens were “struggling to find common ground”, in part because of mistakes the president acknowledged had been made in the process of reunification, he called for a “new solidarity pact of appreciation”. This would be “an imposition”, he conceded, “as appreciating people means accepting those who are different and who think differently”, but he insisted it was necessary, because “those who write off ... other people have already written off democracy.”

The queue for the Nikolaikirche’s afternoon service was long, but those unable to get in could watch on a screen outside. Rev. Bernhard Stief opened by recalling the churches of autumn 1989 filled with people anxious about the situation outside, and he expressed thanks for the Peaceful Revolution that followed the peace prayers. “At the same time”, he continued, “we are filled with anxiety ... at news such as that from Halle”, where that afternoon a gunman had shot two people near a synagogue. "It is perhaps a good sign that in today's peace prayer a war wound will be healed": the inaugural ringing of a new bell, replacing one melted in 1917. Representatives of three citizens' initiatives were invited to speak - the Jewish-Christian Working Group, Fridays for Future, and the refugee rescue association Mission Lifeline - because, according to Superintendent Martin Henker, "they offer hope" in response to the question of "whether we can still be saved." With representatives of the 1989 civil rights groups in attendance, the contemporary activists could clearly be seen as successors. Henker encouraged prayer participants to be hopeful, despite “difficult times”, because “fear, lies, and hate will not have the last word.”

Crowning the day and its theme was the Lichtfest. Roughly 75,000 gathered with candles on Augustusplatz, listening to a few short speeches before placing their candles in large boxes to spell “Leipzig 89”, or marching with them around the ring.[3] Mayor Burkhard Jung initiated a moment of silence for victims of violence in Halle, while President Steinmeier expressed incredulity that someone could attack a synagogue “in this country, with this history, on this day!” Kathrin Mahler Walther, an eighteen-year-old civil rights activist in 1989, recalled the anxieties she and her peers had felt, but emphasized that what citizens had once accomplished “together” they could hope to achieve again. “Thirty years ago, we had to fight for democracy ... we had to struggle against violence. Today we must do so again.” It should be noted that neither she nor any other speaker reduced the revolution to a struggle against the SED regime; it had been a struggle over values, still relevant today. As the 75,000 encircled the city in their candlelight march, they passed artistic inscenations built from light – clearly meaningful, but left up to the marchers (democratically) to interpret.

Though Germany’s Peaceful Revolution can best be dated from 9 October, when Leipzig’s “we are the people” march demonstrated that sovereignty had shifted, the opening of the Berlin Wall on 9 November marked a turning point that likewise invites commemoration. The question of framing has been contentious, though. From 1990 until very recently, Berlin’s commemorations celebrated the Mauerfall primarily as a symbol of Germany’s unification, either without mentioning the attendant revolution or portraying unification as the inevitable and sufficient outcome of that revolution – disregarding implications for the present that have always been emphasized in Leipzig. In 2019, that changed. Whereas in 2014, the official slogan had simply been “25 Years Fall of the Wall”, now it was “30th Anniversary of the Peaceful Revolution – Fall of the Berlin Wall”.

The shift could be seen in memory ‘complexes’ set up at seven sites around the city, which told the story of a revolutionary process beginning in 1982 and continuing to unification in 1990. At Gethsemane Church, visitors could learn about the peace and human rights movements it sponsored in the 1980s. At Alexanderplatz they could immerse themselves in testimony about the demonstration of half a million on 4 November 1989. People could tour the former Stasi Headquarters – now a ‘Campus for Democracy’ – and recall how citizens had stormed the grounds in January 1990; at Schlossplatz, site of the GDR’s parliament, the history of the civic initiatives of 1990 was on display. The week-long programme at each complex featured open discussions of historical themes, opportunities to converse with witnesses, politically charged performances of music and poetry, and much more.

The Wall was important, but primarily as an episode within the broader revolutionary narrative. A public ceremony on 9 November at the Wall Memorial on Bernauer Strasse made this clear. Among the roughly 750 attendees were relatives of those who had died at the Wall, international students in the programme ‘My Europe – Our Common Europe’, and prominent politicians from Germany and other central European countries. The students specified unfulfilled aims of the revolution and implored the assembled officials to work towards realizing them. Students from France appealed: “many of our fellow citizens define their own identities as a differentiation from other cultures. ... We therefore ask our fellow citizens and politicians to listen to one another, to find common ground, to secure a future for our [European] union.” Inviting youth to speak directly to political leaders was a powerful way to link the revolution’s civic engagement to the present. Chancellor Angela Merkel evidently agreed, expressing gratitude for the freedoms Germans and Europeans had earned through the revolution, but warning that “the values on which Europe is based – freedom, democracy, equality, rule of law, respect for human rights – these are all anything but self-evident. They must be lived and defended again and again.” Bernauer Strasse was also the scene of a demonstration that evening in support of democracy in Hong Kong and solidarity with dissidents persecuted in China.

Despite intermittent rain, over 100,000 assembled before nightfall for the speeches and concert at Brandenburg Gate that marked the commemorations’ high point, but speakers were less celebratory than in previous years.[4] Berlin’s mayor, Michael Müller, called on Germans to "be proud of what we have achieved together" despite "mistakes made in the process of reunification." Müller also reminded listeners that the memory of Kristallnacht (9 November 1938) “exhorts us to defend freedom and democracy against current attacks, as populists spread hatred.” Marianne Birthler, a former civil rights activist who directed the Federal Commission for Stasi Records from 2000 to 2011, condemned the AfD for its use of slogans like “Finish the Wende” and “Peaceful Revolution at the ballot box” during recent elections in Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia. For Birthler, “those who let their hatred run free and threaten the lives of others with words and deeds are no better than the Stasi.” The only people with the moral right to invoke the revolution’s language, she argued, “are those who today fight for openness and freedom” – an assertion that garnered vigorous applause.

While in Germany multiple dates provide opportunities for commemorating the revolution of 1989, in the Czech and Slovak Republics one stands out. Both of Czechoslovakia’s successor states observe the ‘Day of the Struggle for Freedom and Democracy’ on 17 November, when police brutality against peaceful demonstrators on Prague’s National Avenue (Národní třída) sparked what became known as the Gentle, or Velvet Revolution. Commemoration in Prague has sometimes occasioned re-enactments of the original march; always it features candles of solidarity with victims of violence, on Národní and elsewhere. Often there have been concerts on Wenceslas Square, and since 2014 an association of civic associations has organized a ‘Freedom Festival’, in which a day-long ‘Korzo’ (promenade) on Národní is the most prominent event. Every ten years – the clockwork is uncanny – the anniversary has also intersected with civic mobilization to defend democracy. The 1999 ‘Thank You, Get Lost’ movement against ‘superannuated’ politicians was founded on 17 November. In 2009 the ‘Inventory of Democracy’ concluded its efforts on that date. For the thirtieth anniversary, the civic initiative ‘A Million Moments for Democracy’ organized a demonstration of over 250,000 to protest threats to the rule of law under Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, a former Communist Party member and secret police collaborator, now billionaire agricultural entrepreneur, and President Zeman, who has promised to amnesty Babiš if he is convicted of misappropriating EU funds.[5]

The demonstration took place on 16 November on Prague’s Letná field, where in 1989 roughly 750,000 had gathered for the revolution’s largest assembly. Participants came from across the country, sometimes holding banners identifying whence they hailed, more often brandishing Czech or EU flags, or homemade political placards. Mikuláš Minář and Benjamin Roll, theology students and spokesmen for Million Moments, moderated the event. Václav Malý, former dissident priest, now auxiliary bishop of Prague, who had moderated the 1989 demonstration, emphasized the gathering’s “spiritual dimension” as an opportunity to renew revolutionary ideals, especially respect for human dignity and truth. Between speeches and performances by other figures of 1989, regional activists shared examples of how they were successfully fighting corruption and apathy. Minář warned that the republic was in danger of becoming like Hungary and Poland if “players” on the “political field” crossed four “red lines”: judicial autonomy, media independence, conflicts of interest, and abuse of power. He called on opposition parties to cooperate more closely and encouraged citizens to find every day a “moment for democracy”, while volunteers distributed leaflets suggesting thirty concrete ways to do this. Echoing Henker (and a long line of Czech thinkers, from Jan Hus to Václav Havel), Minář insisted that “truth, love, and courage will prevail over lies, fear, and indifference.” The demonstration emphasized continuity between the struggles for freedom and democracy in 1989 and the present, and it clearly helped transfer the culture of the revolution to a new generation.

A 17 November "reconstruction" of the march that precipitated the revolution was less successful in that regard. Its organizers wanted to “evoke the atmosphere” of 1989, but they also wanted the event to be “apolitical”.[6] The twin imperatives were incompatible. Though the organizers reiterated part of the original invitation, "Bring a flower with you", and even provided roses to those who did not, they proscribed political placards and banners - which had as much as flowers given the original march its character. Instead of engaging with the present, the reconstruction focused narrowly on a single day of the past, with loudspeakers along the route reciting eyewitness accounts of it. At one point, a police vehicle in the style of thirty years previously blocked a street leading away from the official path, with loudspeakers broadcasting recordings of police warnings from 1989.[7] Between ten and fifteen thousand people participated in the reconstruction, many with children and some even on crutches; the mood was upbeat, and some circumvented the placard ban, but in contrast to previous, politically spirited re-enactments, this one approximated a museum visit. Can one really celebrate a founding moment of democracy without practicing democracy?

Reduction of memory while ostensibly refreshing it climaxed on Národní. Where once commemoration meant candles and flowers offered in meditative silence, the Korzo since 2014 has been a cacophonous circus under the somewhat vacuous slogan “Thanks that we can”. A thirtieth-anniversary observer starting at Wenceslas Square would first notice a small Ferris wheel featuring, instead of chairs, poster boards with biographies of individuals who had opposed Communism. Further on, an outdoor ‘Cinema of Injustice Stories’ screened documentaries about unpleasantries of life under Communism. An outdoor exhibit, “Fragments of Revolution”, showcased reminiscences by famous individuals, while a cage, set up by the association Without Communists, represented Communist oppression. In an ‘educational tram’, the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes offered presentations on the same subject. Alongside the National Theatre the Václav Havel Library hosted speakers amid chairs, tables, bookshelves, and lamps in what it called “Havel’s living room”, while the piazza between the Theatre’s old and new buildings was given to non-profit organizations, each of which had a booth for disseminating literature and chatting with passers-by. Performances took place throughout the day on three stages along the Korzo, actors dressed as riot police of 1989 patrolled the avenue, and at 5 p.m. attendees placed candles along the tramway “in memory of victims of Communism”.

Though the spaces around the National Theatre nodded to democratic engagement, the rest of the ‘Freedom Festival’ on Národní celebrated freedom not in the Arendtian sense of the ability to participate in government, but as mere liberation. The Korzo devoted far more attention to the Communist era that preceded the revolution than to the mass mobilization that was the revolution, and the focus on exceptional individuals further minimized 1989 as a foundational moment for democracy. The revolution was reduced to an instant – a one-dimensional boundary between a dark Communist past and a happy present – and evacuated of content that might today be relevant. Unlike the German commemorations, there was no discussion of anxiety, uncertainty, or mistakes.

Bratislava has its own ‘Freedom Festival’, organized by the Nation's Memory Institute since 2011 to “recall and analyze the era of unfreedom”, but it was overshadowed in 2019 by dynamic commemorations that engaged directly with the revolution. The primary reason was Slovak society’s breathtaking response in 2018 to the murder of Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. Kuciak was killed for investigative reporting that uncovered corruption at the heart of the Slovak government; news of the crime sparked a mass movement ‘For a Decent Slovakia’ (Za slušné Slovensko, ZSS), which called for a new, trustworthy government and coordinated protest in a manner recalling the revolutionary culture of 1989. After the movement secured the resignations of the prime minister, interior minister, and police chief, many of its activists regrouped for a long-term effort to improve political culture by engaging with citizens across the country in non-partisan dialogue about substantive issues and the practice of democracy. Though they do not endorse political candidates, their efforts contributed to the surprising victory of Zuzana Čaputová, an environmental and civil rights lawyer, in March 2019 presidential elections.

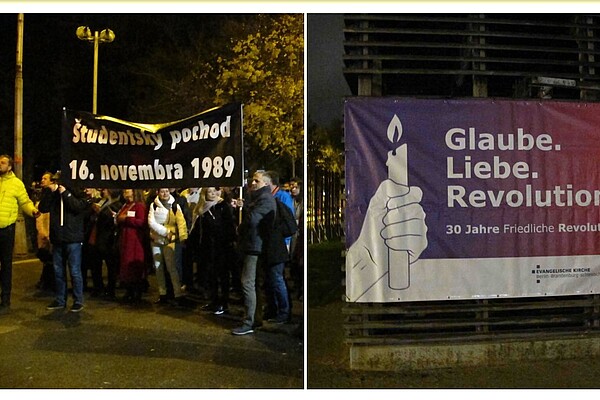

Three significant events took place on 16 November: a re-enactment, a rechristening, and a ceremony in the Slovak National Theatre. For the first time in thirty years, participants in a student protest march on 16 November 1989 decided to retrace their steps, inviting the public to join them. Henrieta Hrinková, who had first proclaimed the students’ demands in 1989, addressed the roughly 200 re-enactors by explaining what had given her courage: “I wasn’t alone. There were no soloists. ... We all trusted one another.”[8] Another former student, Milan Novotný, insisted that like the original march, the re-enactment was to be non-partisan, and he asked those who had brought placards to conceal them. His injunction did not have the sterilizing effect that made the Prague march feel museum-like, however. Instead, this felt like a family reunion. Veterans of the 1989 march held hands as they set out, and en route they shouted revolutionary slogans: “Come with us!” “Freedom!” “We want dialogue!” When the marchers reached the lower half of the Square of the Slovak National Uprising (Slovenské národné povstanie, SNP), they paused to join a ceremony renaming that half ‘the Square of the Gentle Revolution’. Among the speakers here, Zuzana Mistríková, another prominent student of 1989, echoed Hrinková with insistence that every participant in the student strikes had contributed, “without each of them the student movement wouldn’t have been a student movement.” President Čaputová, in her televised speech from the National Theatre, continued the theme, so at variance with the elitism on Prague’s Korzo: “Everyone in the weeks after 17 November who went on strike, organized assemblies, or demonstrated, took a risk and displayed personal courage.” Like Steinmeier, Čaputová confronted reasons why some might not celebrate the anniversary. “The Constitutional guarantee that ‘people are ... equal in dignity and rights’ remains more on paper than it penetrates to reality”, she said, and she highlighted societal polarization as a problem of the present, “even among people with the same values.” “We have achieved ... great societal changes, only when ... we pursued our goal together.” Now “we face a crisis of trust.”

Polarization was apparent in separate commemorative assemblies on 17 November. On SNP Square, Igor Matovič and his opposition party Ordinary People and Independent Personages (Obyčajní ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti, OĽaNO) organized a concert interspersed with speeches by opposition politicians. Ján Budaj, a spokesman for Public against Violence (Verejnosť proti násiliu, VPN) in 1989, whose contemporary miniparty Change from Below has found shelter under OĽaNO’s umbrella, was the first to speak. He read a statement: “We demand a guarantee of the independence of courts and prosecutors and the creation of a state based on rule of law.” “Do you want this?” he asked the thousands present, to vocal affirmation.[9] “But these words are thirty years old! If we had these things there would be no improvised shrine here to two young people”, referring to Kuciak and Kušnírová, whose portrait, surrounded by candles and flowers, stood alongside the square beneath a plaque commemorating VPN. Budaj compared the violence against them to the violence in Prague that had sparked the revolution and emphasized, “we are for a decent country. ... The revolution has not ended.” Matovič reiterated the theme: “We still have something to fight for. The revolution continues in each of us who believes in the ideals of November.” He echoed Minář’s appeal for unity among opposition parties, proposing that larger parties take in smaller ones to prevent their votes from being lost, as OĽaNO had done for Budaj’s party and two others.

On nearby Freedom Square, two hours later, For a Decent Slovakia convened its own commemoration under the banner “Thirty Years Later – Still for a Decent Slovakia”, with perhaps 8,000 in attendance.[10] Here, too, speakers emphasized continuity with the revolution. The former VPN spokesman Peter Zajac called For a Decent Slovakia a new Public against Violence. Robert Mistrík, a candidate in the recent presidential election who had withdrawn in favour of Čaputová, argued that 2019 was as important as 1989, because “we face the danger of being overpowered by mafiosi and fascists.” The whistleblower Zuzana Hlávková invoked the collective ideals of 1989 and, echoing Leipzig’s theme, proclaimed that “freedom is the possibility to overcome fear and take responsibility, but with freedom comes uncertainty.” The actress Kristína Svarinská enjoined citizens not to stop engaging in public affairs with humanity and common sense, because “truth and love always prevail over lies and hatred.” There were cheers for Čaputová and many references to Kuciak and Kušnírová; Zajac declared, “we will pay our debt to them” in the February 2020 parliamentary elections, insisting that members of the governing coalition were “not part of November.”

Despite the passage of time, organizers of thirtieth-anniversary commemorations in all four of our cities found invigorating ways to reanimate the civic spirit of 1989. Sometimes new elements were added to traditional forms of commemoration, as with the restoration of the bell lost to war in the Leipzig peace prayer. Sometimes the forms were altogether new, as with re-enactment of the Bratislava student march. Irrespective of form, much freshness sprang from the anniversaries’ intersection with current threats to democracy, creating a sense of urgent need to reinforce civic vigilance for which the revolutions provide a template.

Thirty years later, it is clear that 1989 gave rise to a new revolutionary tradition. Traditions reinvigorate and reproduce culture most vividly through ritual practices that dramatize collective ideals and identity, and this is why we can discern, with Malý, a “spiritual dimension” in rituals as diverse as the Nikolaikirche services and the Million Moments demonstration. All focused on ethics and individuals’ ideal relation to society; they enabled participants to re-form a sense of community around ideals that could be shared because they were collectively articulated. Typically, they did this by re-enacting (or perpetuating) defining experiences, ranging from the violence on Národní třída to the discussion fora of 1989-90. A distinction can nonetheless be made between re-enactments that filled revolutionary frameworks with current content, such as Leipzig’s Round Table or the Letná demonstration, and those that focused on past frameworks to the exclusion of contemporary content, such as Prague’s 17 November march. At least when it comes to democratic political culture, the rituals that most effectively revitalize it and transfer it to new generations are those that reproduce the original engagement with the present; those that focus on form to the exclusion of animating spirit quickly become routine. “Apolitical” commemoration of the founding of democratic politics can actually undermine democratic politics.

It is impossible to recall all aspects of any past event, but a living tradition can flexibly recall elements relevant for the present. One of the refreshing features of the 2019 commemorations was their emphasis – most explicit in Germany and Slovakia – on the anxiety citizens had experienced in 1989 in consequence of real or potential violence. Those who essentialize the otherness of Communist regimes tend to forget that it was their violence that united citizens against them; incidents like Kuciak’s murder or the Halle shootings provide vivid reminders that unacceptable violence characterizes our societies, too. The revolutionaries of 1989 rejected not just physical violence, but violence in all its forms, and this is why contemporary opposition to environmental violence, chauvinistic nationalism, corruption, lies, and indifference is fully in the tradition of 1989. It is also why the ideals of 1989, invoked in all four of our cities, encapsulate antonyms of violence: truth, love, courage, dialogue, respect for human dignity – and democracy. The revolution was the practice of democracy, and as envisioned in 1989, democracy was to be a means of realizing other revolutionary ideals in communal life – hence round tables, inclusive candidate lists, insistence on equality of rights and the rule of law, emphasis on the choir rather than soloists, marching with candles, not fists.

If the revolution continues among those who believe in its ideals, then indeed, those who hate are no better than the Stasi. The misappropriation of the revolution’s language that Birthler criticized becomes possible only by forgetting that the public of 1989 was the public against violence, and that overcoming violence and its attendant anxieties requires finding common ground (with all the “impositions” that entails). Such forgetting could be seen on Prague’s Korzo, with its portrayal of a revolution that meant nothing more than the end of Communism, and it lurked behind statements dismissing leaders of mainstream parties (like Slovakia’s governing Social Democrats) as “not part of November” without carefully noting that many of those parties’ supporters definitely had “taken risks” and “displayed personal courage” in 1989.

Preservation of accurate memory is necessary to maintain a tradition faithful to its origins, and it is no coincidence that “independent, critical historical research” was the first demand of the Leipzig Round Table’s Memorandum for Freedom and Democracy. The thirtieth-anniversary commemorations suggest that three additional factors can contribute to effective revitalization and propagation of the civic tradition rooted in 1989. Foremost is what Henker identified in his Nikolaikirche sermon as a “perspective extending beyond the next election year.” One reason for the powerful dignity of Leipzig’s commemorations is the central role played by the city’s churches, which interpret the Peaceful Revolution within a multimillenial framework of human-divine interaction that is at once humbling and inspiring, and which informs a principled critique of both past and present. A second factor is dialogue. In his Democracy Address, Steinmeier stressed that we are “the sum of our stories.” The most stirring commemorations of 2019 were those that brought narrators with diverse stories into dialogue, whether between generations, as in the Million Moments or Decent Slovakia assemblies, or simply among those with differing experiences of the revolutions, as with the memory ‘complexes’ in Berlin. Finally, though cultivation of democratic tradition does not depend on support from political officeholders (as the Czech example clearly shows), the active participation of the German president and chancellor, or the Slovak president, definitely reinforced a wholesome relationship between civil society and the state. If, as Birthler insisted, not everyone has a moral right to invoke the revolution, it is a good sign when the right of political officeholders to do so cannot be disputed.

The fact that Steinmeier – a West German who participated in the Peaceful Revolution only vicariously – could so faithfully and forcefully promote the revolution’s ideals underscores those ideals’ potentially universal significance. Perhaps most intriguing was Steinmeier’s suggestion that the 1989 revolutions prefigured “the democracy of the future”. The revolutions demonstrated that it is violence – pure and simple – that gives us anxiety, and that this anxiety can be overcome through fellowship – which is democracy – which is freedom. Achieving this kind of strength through unity requires respect for human dignity and for truth, since no consequential dialogue is possible otherwise. As Čaputová observed, the polarization of our time that prevents dialogue reflects a crisis of trust. Whether we can overcome this crisis – whether, in other words, we will have democracy in the future – may therefore depend on how we answer a simple question. Do we really believe that truth and love will prevail over lies and hatred?

Funding for the research behind this article was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber: The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. In: Cultures of History Forum (29.05.2020), DOI: 10.25626/013.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

Patrick Metzler · 21.12.2022

Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Karolína Bukovská · 25.11.2021

(Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twent...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).