04. Mar 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0095

Verena Meier is a PhD candidate at the Research Center on Anti-Gypsyism (Forschungsstelle Antiziganismus) at the University of Heidelberg. Among other, she has been assistant to the curators of several exhibitions at the Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg and worked at the Documentation Center of North African Jewry during WWII at the Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem, Israel. Her research focuses on the history of minorities, the history of ideas, and on historical stereotypes.

‘Racism. The Invention of Human Races’ was the title of a temporary exhibition at the German Hygiene Museum in Dresden from 19 May 2018 to 7 January 2019. According to the museum’s annual activity report for 2017, the exhibition makers set themselves two goals: first, the curators aimed to provide information about the construct of ‘races,’ the distribution of this construct in popular culture, and its consequences for the people affected in the context of unequal power relations and diverse societies. Second, they intended to draw attention to the museum’s own history and role in promoting racial ideologies and racialized thinking. Informed by postcolonial theory and with the help of a considerable number of artefacts and objects, mainly from their own archives, the museum offered a critical reflection on these issues and the implications of racialized thinking up to the present day. The exhibition is an example of how museums and curators can engage critically with their institution’s history not only on the level of content – what narrative is told – but also on the level of methodology – how this information is conveyed.

The exhibition was spread over roughly 800 square meters, structured in four distinct thematic sections: the first section, or prologue, addressed the question “How different are we?” by telling the story of how racial classification systems developed and how difference has been constructed since the Enlightenment in the eighteenth-century; the second section was entitled “Where do we see ‘races’?” and was dedicated to the educational material and exhibitions displayed by the Hygiene Museum, as well as other exhibitions, during the period of National Socialism in Dresden; the third section focused on the violent history of colonialism and a world order in which “the other” was constructed by answering the questions “Who are we? Who are they?” The last section asked, “How do we want to live together?” and provided room for reflection on the state of current societies.[1]

Upon entering the first exhibition room, visitors found themselves in a dimly lit room with the objects illuminated in cubes placed within tall wooden constructions. As the subtitle to the entire exhibition makes plain, a major aim of the curators was to show how ‘races’ are constructed. Among the very first exhibited objects is a suitcase belonging to ghost hunters. It is contrasted with the measuring devices used to ascertain an individual’s ‘race’ in order to highlight the constructed nature of both phenomena. Initially, the curatorial team considered titling the entire exhibition “Phantom,” which suggests an equalization of ‘races’ with phantoms. Thanks to the advisory council, made up of political activists and minority-led organizations, the title was changed to ‘Racism. The Invention of Human Races.’ The advisory council’s main point of criticism was that racism is not just a phantom, but that it causes real physical and mental consequences for the people affected by it.[2]

Further objects and drawings on display elucidated the creation of anthropological ideal types in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the consequences of these constructs, and presented the reactions of people who were classified as ‘inferior.’ The main exhibits on display included instruments for measuring and documenting skin, hair, eye colour, and other body parts, tables, photography tools and anthropometric photographs, plaster casts and other objects used for the purpose of classifying human ‘races’ with the help of ostensibly scientific methods. They all demonstrate a racialized thinking that expressed itself in the creation of arbitrary categories that were ‘scientifically’ analysed.

This categorization is also reflected in the design of the first room, which makes use of a wooden installation in the form of a shelving system. On the level of content, the curators break with these rigid racial categories by means of artistic outputs against racism (paintings, music videos, literature and the like) or interviews with affected individuals, such as the US Civil Rights-era activist and writer James Baldwin, reports by colonized people who were subject to racial-anthropological examinations and interviews with individuals who reflect the diversity of German society. Such audio-visual and artistic objects can be seen as tools of ‘writing back’ and providing a counter-narrative. This technique has been used by post-colonial writers and artists aiming to re-read and re-write the historical and fictional record produced by, drama, fiction, historical accounts, the journals of explorers, and maps in order to subversively break with dominant discourses and open up different views on these specific texts from the perspective of the periphery. It is thus a critical engagement with texts or artefacts that were produced by colonizers, inscribing them with new meanings through this process of integrating a counter–narrative and including the voices of those who were subjugated through these texts and artefacts.[3]

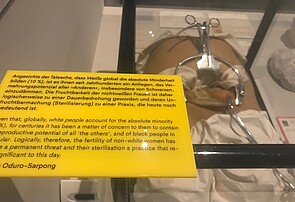

Such post-colonial practices were also taken up in the exhibition. They involve, for example, ‘interventions’ with comments by individuals affected by racism and discrimination. These thought-provoking comments, mostly in the form of yellow signs, were placed next to the objects in order to reflect a counter-narrative, sparking self-reflection on the part of the readers. According to the group of activists who participated in the creation of the exhibition,[4] these interventions were a late but necessary addition to the curators’ overall narrative, since the reproduction of racism also leads to exclusion and devaluation.[5] This dual narrative creates a feeling of cognitive dissonance, which can be seen, for example, in the display of anthropologist Felix von Luschen’s collection of hair samples, gathered in 1900 for his book Introduction for Scientific Observations in the Fields of Anthropology, Ethnography, and Primeval History (published in 1914). In the book, von Luschen explains how to gather material for observation in the colonies. The presentation of both the hair samples and the book in the exhibition is interrupted by an intervention by the activist Mnyaka Surura Mboro, founding member of the association Berlin Postkolonial, in the form of a comment on a yellow strip placed next to the exhibited object. Instead of uncritically re-exhibiting the racist material, the comment by the activist thus reminds the visitor that the objects on display were collected by measuring and examining “our great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers” and that “our ancestors are still on display in museums.”

Chipping away at racialized perspectives is accomplished in multiple ways throughout the first part of the exhibition – by placing veils over plaster casts or by including audio statements by affected individuals in booths that are separated by transparent shields with ethical questions written on them: “What do we want to show? What are we allowed to show and what not? How do we show something without ‘putting it on display’?” The visitor’s attention is thus drawn to the ethical dilemma of re-exhibiting such racist objects – most of them acquired in contexts of subjection and usually without the consent of the person affected – and thereby reproducing racial stereotypes by exhibiting them again in museums today. Beyond this meta-reflection on the exhibition of such objects, the architecture of the installation is notable. Visitors can only reach the audio station by going underneath a shield, thus requiring some degree of physical immersion in the exhibition.

Due to the multifaceted nature of the phenomena of ‘race’ and ‘racism,’ differentiations between time, place, and experiences as well as distinctions between different forms of racism or hatred against different groups of people are elided. Modern genetics are discussed alongside eighteen-century racial examinations and reports from the civil rights movement in the United States are displayed alongside studies of phrenology and the categorization of races and socially peripheral humans, such as criminals in post-Enlightenment Europe. The exhibition touches on different manifestations of racism, but – due to the didactic reductions all exhibitions make – visitors are confronted with a kaleidoscope of expressions of racism.

Moving into the second section, visitors are introduced to the Hygiene Museum’s own role in the distribution of racialized thinking, which is contextualized through the inclusion of other exhibitions also held during the Nazi period in Dresden. The current director of the Hygiene Museum, Klaus Vogel, acknowledges that through the ‘Racism’ exhibition the institution is attempting to deal with its own “contaminated past” – a past which cannot be circumvented. It is the museum’s first self-critical exhibition wherein it addresses its own racist past. Previously, the institution’s role in disseminating racist rhetoric was part of “Deadly Medicine. Creating the Master Race” (Tödliche Medizin. Rassenwahn im Nationalsozialismus), shown in 2006-2007 – but that exhibition was developed by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[6]

The museum as an institution was initially envisaged as a place for educating the general public on health care and living a wholesome lifestyle. In 1912, founder Karl August Lingner (1861-1916) wrote in a memorandum: “The museum shall be a place of teaching the whole population, where everyone can obtain insights through viewing [exhibitions], which will enable him to a rational and wholesome lifestyle.”[7] Yet the cornerstone of the museum was only laid in 1930 after Lingner’s death. In addition to permanent and temporary exhibitions, the museum was to include rooms for public lectures, and workshops where exhibits and illustrations could be produced. The museum opened with the “Second International Hygiene Exhibition.” Topics such as “heredity and racial hygiene” that had become important during the 1920s served as anchor points for the museum’s exhibitions and the production of educational material in the workshops.[8]

During the Nazi regime, the German Hygiene Museum served as an amplifier of racialized and racial hygienic thinking in line with National Socialist racial ideology and propaganda and underpinned by ostensibly scientific explanations. In the recent exhibition, visitors engaged with the educational material on “racial theories”, “hereditary health” and eugenics produced by the Museum under National Socialism, as well as gaining insights into the Museum’s travelling exhibitions, including “New Eugenics in Germany,” shown in the United States in 1934, and “The Miracle of Life” (“Das Wunder des Lebens”), shown in Berlin in 1935. The National Academy for Race and Health Care, a research and educational institution, was linked to the German Hygiene Museum in Dresden and responsible for the production of racial political propaganda.[9]

In addition to shining a light on the museum’s promotion of National Socialist racial ideologies, the recent exhibit included materials from “Degenerate Art” (“Entartete Kunst”), an exhibition shown in 1933, and the “German Colonial Exhibition,” shown in 1939 at the Dresden city hall. On display was also propaganda material produced in-house by the Museum.[10] This second section of the exhibition differed from the previous section not only in its specific regional focus, but also in its design. Concrete walls and showcase bases dominated the section, in contrast to the wooden installation of the first section. The exhibited moulage of a female uterus demonstrated the interdependence between the museum’s collection of educational materials and objects and the violent practices of exclusion inherent to Nazi ideology: It visually represented a sterilization method suggested by Albert Döderlin in his commentary on the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases from 1934. The moulage was created in an unknown workshop but is part of the museum’s collection. As in the previous section, interventions continued to be part of the exhibit. Here, the intervention hinted at the long history of attempts to contain the reproductive potential of those individuals deemed ‘other.’ A deeper reflection and differentiation on the differences between today’s ideas and practices about state control over fertility, and those of the colonial or National Socialist periods was, however, missing. Self-critically, the exhibit also displayed educational material produced in its own workshops – such as graphic educational posters that visualize the heredity of diseases, “inferiority” or “insanity” – next to propaganda boards elucidating cultural differences between “races” and propaganda material about the “Jewish race”. It thus drew a connection between racial, racial-hygienic and eugenic ideas, while simultaneously referring to the violent practices that followed from it, such as the murder of patients from psychiatric hospitals in Nazi gas chambers as part of the ‘T4-Aktion,’ begun in 1940.

Audio stations at the end of this section gave visitors the chance to listen to reports and documentary clips by and about different groups of people who suffered from racism and discrimination. Entitled “Fighting for commemoration,” these reports illustrated the difficulties many victim groups faced after the Second World War to be recognized as victims of the Nazi regime. Again, the exhibition did not highlight the nuances and differences between different forms of antisemitic, antigypsyist, or homophobic discrimination (among other forms of oppression). By clustering all these forms of hatred together without a deeper differentiation, the different positions of the ascribed ‘other’ were neglected,[11] and the different facets of antisemitism – anti-Judaism versus modern antisemitism versus anti-Zionism – or of antigypsyism were not made apparent. The Nuremberg Laws could have, for instance, served as a springboard for discussing the different forms of racism, their manifestation and practical implications during the Nazi period in a comparative way. Limiting the phenomenon of antigypsyism to two video clips from after 1945 and the struggle for recognition as victims of Nazi genocide, and not including the attempts of the medical professionals at the ‘Racial Hygiene Research Centre’ to construct a ‘gypsy race’ was, thus, a clear shortcoming.

The third section turned again to colonialism. It asked “Who are we? Who are they?” and discussed the violent rule over the colonies from a postcolonial perspective. It also highlighted the relationship between racism and geopolitics, the construction of ‘the West’ and its supposed superiority over an inferior ‘Orient.’ The exploitation and subjugation that continues to exist are displayed through photographs, quotes, movie clips, interviews, and digital maps. As a counter-narrative to the ‘Oriental’ or colonized view, images of the imagined ‘other’ were contrasted with portraits and pictures that present an emancipated self-image. Current issues, such as the global migration and the restitution of objects in European museums that were appropriated through colonial domination, highlighted that colonialism did not end with decolonization.[12] The curators again situated the local history of Dresden in a wider post-colonial context. This is exemplified in the model of the Yenidze tobacco factory, which was built in 1909 in an Oriental style, and resembles a mosque. Critical reflections on such imagery in this section clearly reflected the key works of postcolonial studies – a diverse, interdisciplinary, transnational field of research which aims to decentre Europe and the West in its analysis. Literary critic Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) is regarded as the foundational study for the field. Using Foucault’s discourse analysis and his notion of the interrelationships between knowledge and power, Said describes how dominant cultures such as Western colonizers represent and construct subordinate cultures and thereby manifest their power positions. Said highlights that the ‘Orient’ was not solely imaginary but also became an integral part of European material civilization and culture, giving rise to specific institutions, vocabularies, and bureaucracies.[13]

The manifestation of this phenomenon in society and material culture was shown through the eyes of the people affected. In segments of the documentation series ReMIX, produced by Nadja Ofuatey-Alazard and directed by Nicolas Grange, local people are interviewed at places of remembrance in four former German colonies in Africa. They were asked about issues such as slavery, Christian missionization, medical experiments, economic exploitation, forced labour, war, and genocide as well as anticolonial resistance. In addition, curator Volker Strähle conducted interviews in Namibia and Tanzania for the conference “Prussian Colonial Heritage. Sacred Objects and Human Remains in Berlin Museums” (15 October 2017), which were included in this exhibition. These interviews all dealt with the overarching question of colonial legacies in former colonies in a postcolonial world.[14] In 1961, the philosopher, psychiatrist and revolutionary from the French colony of Martinique, Frantz Fanon, postulated in his book The Wretched of the Earth that the first step for colonialized people is to find a voice and identity so that they can reclaim their own past.[15] This struggle for decolonization and reclaiming the past in the former colonies became vivid through these interviews.

The final section dealt with the question of “how do we want to live together?” by undertaking another curatorial break in the third room. Architect Diébédo Francis Kéré produced an artistic installation out of cardboard tubes that covered and divided the entire room. Originally from Burkina Faso, the architect created an installation inspired by places in Burkina Faso that serve as spaces for communication for a community:

Based on traditional architectural forms and practices from my home country Burkina Faso in rural West Africa, this architectural installation for the last room of the exhibition has analogies to treetops. They form the roof, the protected space and social centre of village life. Here the community meets, shares the experiences, tells stories. [...] In general, I understand the spatial sculpture for this exhibition as a symbolic centre for communication.[16]

This entire section – in its content as well as in its scenography – is to be understood as a room for reflection, communication, and engagement with the interviews projected within. The curators and the architect invited the visitors to initiate discussions while surrounded by the cardboard tubes of this spatial sculpture reminiscent of the symbolic communication centres in Burkina Faso. Furthermore, in this section, only film clips specifically produced for the exhibition were shown, all meant to highlight the experiences of people facing discrimination. Sketches of life in pluralistic societies were outlined out and visitors invited to engage with their own diverse social reality.[17] One film shown in this section, “Your Gaze – Dein Blick” by the Dresden-based video artist and filmmaker Barbara Lubich, includes portraits of different people and has them tell three fundamentally different biographical stories about themselves. The question – which one of these stories is correct? – is only answered in the last minute of the eight-minute short movie. By doing so, she intends to place a mirror in front of viewers’ expectations and prejudices.[18]

According to President Frank Walter Steinmeier, who visited the exhibition in November 2018, this was one of the more important exhibitions to be seen in Germany over the past years. Steinmeier combined his visit to the exhibition with meeting students and other citizens, both in Dresden and Chemnitz and to talk with them about recent incidents of open racism in Germany. His visit showed the high level of political relevance that was attached to this exhibition in Dresden, a city that is the birth place of the right-wing movements Pegida – a fact that was repeatedly highlighted by local and national newspapers.[19] In contrast to this perception, however, Klaus Vogel insisted that it was the realization about the Hygiene Museum’s own historical role as an amplifier of racialized thinking, rather than current political events that had motivated the museum to put up this exhibition.[20] However, recent racially motivated violent attacks as well as rapant racism especially in the social media show how necessary such an exhibition was.[21] According to the museum’s website, by November 2018 the exhibition had been seen by over 60000 people, among them several thousand students.

In the exhibition, the museum presented the complex phenomenon of racism through the centuries in a nutshell and included critical reflections on Dresden and the Hygiene Museum’s role in promoting racialized thinking and counter-voices by the people affected. All this was presented by means of an interesting design concept and was supported by the use of various forms of (participative) multimedia, such as videos that had been produced specifically for the exhibition. In response to the necessity for didactic reduction, racism as phenomenon was however presented more by highlighting separate phenomena or distinct developments than by developing a single concise narrative. Thus, the exhibition walked us through the racial examinations of the eighteenth century; the production of propaganda material and exhibitions produced by the Hygiene Museum during the Nazi regime; colonial violence, exploitation, and independence movements; the imaginary ‘Orient’ and, finally, the future in pluralistic societies.

Thus, in line with Britta Schellenberg’s assessment, it would have been useful to include references to academic debates – including recent findings about different forms of racism (individual, institutional, structural, discursive and cultural; intended and non-intended) or the effects of racism on individuals, groups or entire societies –in order to reveal the different aspects of racism and contextualize it in a larger discussion.[22] Furthermore, the entangled histories of the National Socialist regime and German colonialism are not reflected upon critically in the exhibition, due to the spotlight nature of its presentation style.[23] However, the exhibition was able to embed many objects from the museum’s own collection and to critically address the city of Dresden and the institution’s role in promoting racialized thinking. It thus clearly showed that racism manifests itself not only in colonial policy or on the state level, but also on a local level. A postcolonial perspective and different modes of narration with thought-provoking interventions (by means of printed comments, art and the stunning design of the exhibition) provide a fully immersive experience of the exhibition – physically, cognitively and emotionally. Finally, the exhibition catalogue serves as a valuable complement as it also discusses some of the exhibitions’ conceptual ideas and invites the reader to take a closer look at images and sources that promote and circulate racialized thinking: It is only with the help of an enclosed piece of orange plastic paper that the reader is able to fully see the edited pictures. Editing the pictures and making their contents invisible at first glance can thus also be seen as an intervention, which forces the viewer to see these images in a new light, distanced from their usual viewing habits.

Verena Meier: The German Hygiene Museum’s exhibition ‘Racism. The Invention of Human Races’. In: Cultures of History Forum (04.03.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0095

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

Matěj Spurný · 31.10.2021

The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as ...

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).